Sitting across from me on a veranda at an African College was a young woman in her second year at the university. She has a warm smile and a slightly shy aura. Her English is good, and her accent is understandable. (A plus because my hearing is not great.) I will call her “Missy.” Missy has a hard story to relate and only after I ask several strategic questions are we finally getting to truly important matters.

Missy has two older sisters. They are seven and five years older than her respectively. Both are married and live in different villages. Early in their marriages both invited her to stay with them. On different occasions, and when her sisters were out of the houses, both of her brothers-in-law individually raped Missy. Horrific experiences. Blood boilingly awful. To add insult to injury, Missy’s sisters deny that these incidents ever even happened. “My husband would never…”

All of this is told through tears, but with strength that inspires.

Missy’s underlying question is, “How can I move forward in life?”

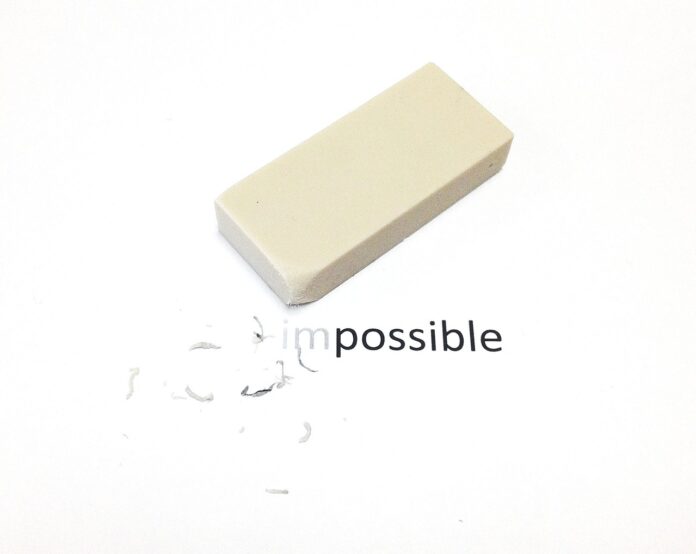

My answer: “First, identify what is impossible.”

Arthur Conan Doyle’s character, Sherlock Holmes, said, “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.”

This approach is invaluable to solving mysteries, but also has application in many directions, including dysfunction within families (and as we will see, in financial services).

Missy faces a dilemma:

- Either she can grow bitter, bear resentments, and nurture hate toward her attackers and her sisters; or,

- She can forgive her attackers to their faces and forgive her sisters to their faces for denying what happened.

I ask, “Missy, we cannot change the past, so what do you want in your future?”

“I desire to have my family around me and do not want to see it all broken apart.”

I tell her that choice number one—sitting in bitterness, unforgiveness, and hate—will make her dream impossible. Alternatively, extending grace (unmerited) and forgiveness (undeserved) is the path forward to achieve her desires. (This option is unnatural and may require God’s help.)

Point: When faced with hard issues, challenges, and difficulties, the way forward begins with discovering, then eliminating, the impossible.

Financially Impossible

The United States is $34 trillion in debt. Getting out of debt seems to me to be undeniably impossible. But I digress.

As an independent financial professional (IFP), you meet innumerable people whose financial situations appear extremely bleak. In order to give them practical, executable action steps, you must first eliminate the impossible.

Case Study #1:

You get introduced to Darrin, age 45. He is an extroverted guy with a nervous demeanor. His wife Susan, age 46, is the friend of one of your clients and, having heard of the good work you did for her friend, contacted you requesting your assistance with her own family’s finances.

You look around. Nice four-bedroom house on a broad wooded property. Two late model cars on the circular driveway. “Must be doing pretty well,” you think to yourself.

You ask an opening question: “Who has been your financial advisor?”

“We have never used one,” says Susan. “Neither wanted nor needed one,” says Darrin. (Yellow caution flag.)

“Of the financial institutions you have worked with, which has been your favorite?”

Susan looks at Darrin, who says, “I really don’t trust any of them.”

“Exactly how have they disappointed you?”

“Too many restrictions,” says Darrin. (Yellow caution flag.)

You decide to switch tactics. “Tell me about your financial goals.”

Susan: “We want to retire while we are still young to a state with a warmer climate and near beautiful water where we can attract visits from our grandchildren!”

Darrin: “Retirement. That will be the day.” (Big red flag.)

After asking Darrin a series of questions designed to peel back the layers, you and Susan are simultaneously introduced to three pieces of bleak news:

- Darrin has nothing saved for retirement.

- Darrin has been a compulsive gambler. In fact, he cashed in their CDs before the end of their terms and gambled away those monies. He borrowed funds from his 401k by finagling his answers to the questions as to the use he intended to make of them.

- He took lines of credit against the house over and above the mortgage.

The Impossible: Retiring at a younger age and purchasing a beachfront condo.

The probable: While most IFPs recommend that young people save 10 percent to 15 percent of their incomes toward retirement, they also know that people in their 40s earn 60 percent more than they did in their 20s. People in their 40s and even 50s who are not on track can often catch up by saving a larger percentage of their income. Because Darrin earns a strong income, and the combined total loan payments are less than 30 percent of his income, there is a strong possibility that Darrin and Susan can get on track to retire in Darrin’s mid-to-late sixties and be able to afford a place, while maybe not on the beach, perhaps four blocks from the beach. Regaining financial footing will require the following:

- Counseling for Darrin’s gambling addiction.

- Great accountability.

- Transparency.

- Susan acting as a co-signer on all accounts.

- Significantly increasing the savings from each month’s income.

Unsurprisingly, forgiveness and grace will also be required!

Case Study #2:

You were recently introduced to Pickleball. You had no idea how popular the game had become until you heard so many people talking about it. At the invitation of a neighbor, you tried it out. And loved it! Your enthusiasm led you to join a kind of league. Now you meet innumerable people who are like-minded and have equivalent skills.

One such pickleball fanatic is Robert. At age 42 he seems no older than…age 62. He is not in Olympic shape, let’s leave it at that. As a successful IFP you know when to begin asking probing questions.

“Tell me about your family,” you say.

“Well, which one?” he responds. Letting you absorb this in a moment of awkward silence, Robert says, “You see, Debbie and I raised two children, and they are on their own, married, and beginning their families. They are fully fledged!”

You mean it when you say it, “That is great news! Congratulations!”

Robert continues. “Then, the unexpected happened. We met a young woman desiring to end the pregnancy in which she was carrying twins. We urged her not to go through with the abortion she was contemplating. She agreed upon one condition. Debbie and I would have to adopt, and raise, her twins.”

“Ufda,” you say. (Your deceased Norwegian parent still impacts your life!)

“Well, we are delighted, actually, and we feel like we have brand new purpose,” says Robert.

“If you don’t mind me asking,” you hesitantly begin, “How has this impacted your financial lives, like retirement goals?”

“Most of it went out the window!” Robert does not look unhappy. “I will be 60 when the twins graduate from high school and start college.”

“Well, I already used up my Ufda.” Then you venture into the wild unknown, the land of no return. “Do you still own life insurance?”

Now Robert looks serious. “You know, I don’t. We had buckets of term life insurance that we let lapse when our kids were launched. I guess I should consider this. Do you sell life insurance?”

“Sorry, no,” you lie. “I mean, I secure life insurance for clients that need/want it, but I am not a salesman per se.”

“Gotcha,” replies Robert.

You and Robert meet again later, this time not on the Pickleball court. You discover that in addition to carrying a few extra pounds, Robert has Type 2 Diabetes. And, he has a family history of heart disease.

You secure some quotes for 20-year term from a few leading carriers. The rates are something like ten times what he paid prior to dropping his long-held policies.

“These premiums are a bit off-putting,” you observe. “Tell me. Would you have agreed to adopt the twins if you didn’t think you could provide for them?”

Robert looks intrigued. “Of course not.”

Taking a deep breath you ask, “Then you are committed to doing so, even if you die prematurely?”

Robert nods. “It would be impossible to do so unless I owned sufficient life insurance, wouldn’t it?”

“Yes,” you say, and then, “It’s the impossible we want to eliminate first. Now that we have done away with the impossible, we can investigate what’s possible.”

Point: Most family and individual financial crises are partial failures, not complete; financial stress usually involves temporary setbacks and not permanent. This is the basis of something being probable, and not impossible.

Financial A Fortiori

In philosophy, there is something called an a fortiori argument. It is defined like this: “If something less likely is true, then something more likely will probably be true as well.”1

Example: “Jesus used an a fortiori argument when He said, ‘If you, then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask Him!” (Matthew 7:11) Jesus’ point hinges on the phrase how much more.”2

As an IFP you encounter potential clients who cling to an idea even if it is indubitably false. One such idea is the amount of life insurance that someone should own in order to be a prudent provider for his or her family.

Case Study #3:

A successful female executive says, “I think about $500,000 is the right amount of life insurance given our circumstances.”

Facts:

- She makes $112,000 per year.

- She has a husband who is on disability from the Police Department. He gets a minor monthly stipend. He is on a prescription for a neurological treatment that costs in excess of $1,200 per month out of pocket.

- There are two children aged 13 and 10. They are each in the “Fast Track” program at their schools. They expect to go to college.

- The kids’ combined private school tuition (partially subsidized by the school in honor of her husband) is still $1,200 per month.

- The monthly mortgage payment is $1,150 and the outstanding loan balance is $395,000.

- Total household monthly budget for basic expenses is slightly less than $6,000.

- They have $28,000 in their savings.

As an IFP you could make an a fortiori argument along these lines:

“If you died without life insurance your family’s savings of $28,000 would be used up in less than six months. Where would that leave them? On the other hand, if you died owning $500,000 of life insurance, your family’s expenses would be covered for less than seven years. If leaving them destitute after five months is unacceptable, how much more acceptable is leaving them destitute after seven years?”

The a fortiori argument in this case is, “If it places your family in an impossible situation in only five months without life insurance, is delaying an impossible financial situation by seven years more acceptable?”

There is a stronger use of a fortiori argument. “If you believe that $500,000 is ample, and your family could struggle by, then how much better would it be for them if they had $1,000,000?”

Point: In financial services we benefit our clients when we first identify, and eliminate, what is impossible, and second, by using a fortiori arguments, helping them see what can be possible, even probable, and in fact, preferable.

Summary

An IFP’s responsibility is to root out the impossible and to make plain the probable. In essence, as an IFP, to best help your potential clients who are currently in financial crisis, “Identify what is impossible.” Then eliminate that.

Next, employ the very useful skill called a fortiori argument in order to persuade clients regarding what is truly possible.

“The ancient Romans utilized argumentum a fortiori, ‘argument from strength.’ Its logic goes like this: If something works the hard way, it’s more likely to work the easy way. Advertisers favor the argument from strength. Years ago, Life cereal ran an ad with little Mikey the fussy eater. His two older brothers tested the cereal on him, figuring that if Mikey liked it, anybody would. And he liked it! An argumentum a fortiori cereal ad.”3

Much of the procrastination that occurs in families putting off financial planning decisions stems from the fact that the waters are murky. There are currents of impossibility flowing just below the surface.

Financial issues are usually not completely beyond solving, and rarely final.

Sherlock Holmes: “It may be that you are not yourself luminous, but that you are a conductor of light. Some people without possessing genius have a remarkable power of stimulating it.”4

I say, regardless of what your clients believe about their circumstances, shine a light on the possibilities, and that will have inestimable consequences in their lives and yours.

Footnotes:

- https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-fortiori 1689072#:~:text=Examples%20and%20Observations,probably%20be%20true%20as%20well.%22.

- https://www.gotquestions.org/a-priori-posteriori-fortiori.html.

- “Thank You for Arguing: What Aristotle, Lincoln, and Homer Simpson Can Teach Us About the Art of Persuasion,” by Jay Heinrichs, 432 pages, Kindle Edition, First published February 27, 2007.

- “The Return of Sherlock Holmes,” by Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes Series, Publisher: Book-of-the-Month-Club, Release Date: January 1994, ISBN: B000B11TGC.